training - consulting - facilitating

get answers to some common questions

Climate Change and Greenhouse Gases

Is climate change really happening?

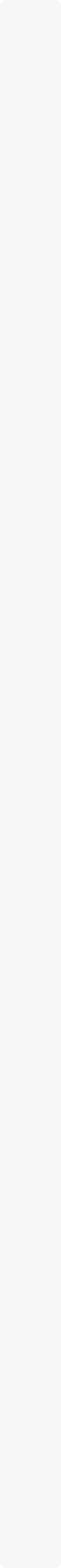

Scientific evidence confirms that human activities, such as burning fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas), agriculture and land clearing, have increased the concentration of greenhouse gases (GHG) in the Earth’s atmosphere.

answers to some frequently asked questions about climate change

to find out more - simply click on the icon links on these pages or click on the documents to download the files

link to UNFCCC Copenhagen Accord

link to UNFCCC

link to Kyoto Protocol

link to IPCC

find out more about

climate change science by

Federal Government

Clean Energy Future

website

the IPCC periodically releases updates on climate research and predictions of future effects if trends continue

the Kyoto Protocol is regarded as the breakthrough global agreement to tackle climate change

economists believe that an ETS is the most cost-effective way of managing carbon pollution in a carbon-limited economy

political manoeuvrings in Copenhagen prevented new post-Kyoto limits being agreed upon - the haggling continues but new binding targets yet to be committed to

on the 10th July 2011 the Australian Government announced a major new climate change policy and tax package

a carbon tax on the 500 largest emitters is to start 1st July 2012 and evolve into an ETS in 2015

land clearing rates in Australia in 1990 were substantially higher than in years immediately afterward - the 8% increase plus large decline in land clearing rates since has allowed Australia to significantly expand its energy sector yet still meet its Kyoto commitments

download PDF

if current trends continue the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere is predicted to double by 2050

GHGs warm the Earth’s atmosphere by absorbing and emitting radiation within the thermal infrared range, causing what is called the ‘greenhouse effect’ or ‘global warming’. The primary greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are water vapour, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and ozone.

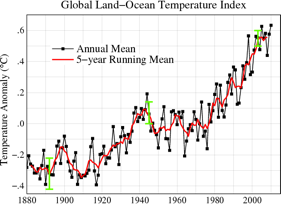

There are six ‘anthropogenic’ (meaning ‘caused by human activity’) emission types that are included when talking about GHGs. They are carbon dioxide (CO2), sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and perfluorocarbons (PFCs). The contribution of these gases to atmospheric warming (or ‘global warming potential) is measured relative to that of CO2 (expressed as CO2 equivalents).

In 2011 the average atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) reached 391 parts per million by volume (ppmv), representing an average increase of approximately 2 ppmv per year for the last decade. The average atmospheric concentration of CO2 in pre-industrial times (~the year 1800) of 260-280 ppmv had stabilised in that range for the preceding 10,000 years.

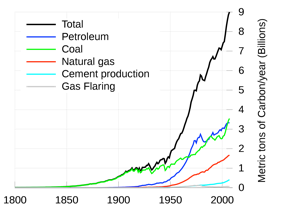

As a consequence of increasing GHG in the atmosphere, the Earth’s average temperature is rising; causing changing weather patterns, affecting rainfall, water availability, sea levels, storm activity, droughts, bushfire frequency plus increasing ocean acidification and affecting marine ecology. This puts at risk coastal and inland Australian communities, population health, agriculture, fisheries, food security, biodiversity, tourism and heritage for current and future generations.

The general consensus amongst the worlds leading science organisations is that human-induced climate change is happening and action should be taken to minimise the effects. Despite the accumulated scientific evidence, there continue to be many who do not believe the science and dispute the need to take any preventive action.

International community response

A number of international organisations and intergovernmental agreements have been established to evaluate the scientific information and guide policy formulation for global and national action to mitigate human-induced climate change.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) established in 1988 is the scientific organisation charged with reviewing and assessing the scientific evidence for risk of human-induced climate change and to provide advice to the international community on the potential environmental and socio-economic consequences. The IPCC does not fund climate science, it simply reviews and reports on scientific progress in climate change research.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) established in 1992 is the intergovernmental agreement that aims to stabilise GHG concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous interference with the climate system. The agreement includes an obligation on Australia to ‘adopt national policies and take corresponding measures on the mitigation of climate change, by limiting anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases and protecting and enhancing its greenhouse gas sinks and reservoirs’. This establishes an overall obligation on national governments to do something to minimise emissions.

The Kyoto Protocol (1997) is an international agreement linked to the UNFCCC. The major feature of the Kyoto Protocol is that it set binding targets for 37 industrialised countries for reducing GHG emissions.

The major distinction between the Kyoto Protocol and the UNFCCC is that while the UNFCCC encourages industrialised countries to stabilise GHG emissions, the Kyoto Protocol commits them to do so with binding targets.

Recognising that developed countries are principally responsible for the current high levels of GHG emissions in the atmosphere as a result of more than 150 years of industrial activity, the Kyoto Protocol places a heavier burden on developed nations under the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities.”

Under the Protocol, countries must meet their targets primarily through national measures. However, the Protocol offers additional means of meeting targets by way of three market-based approaches:

-

•Emissions Trading Schemes

-

•Clean Development Mechanism

-

•Joint Implementation

Emissions Trading Schemes (ETS) allow countries that have spare emission units - from each country’s total ‘allowed limits’ or ‘cap’ but that are not ‘used’ - to sell these spare units to countries or businesses that exceed their allowed limits. This creates a new commodity in the form of activities that reduce (save) emissions or activities that remove (sequester) carbon from the atmosphere. As CO2 is the principal greenhouse gas, it is referred to as ‘trading carbon’ and the tracking and trading of carbon has become known as the ‘carbon market’.

More than actual emission units (each unit is equal to one tonne of CO2) can be traded and sold under the Kyoto Protocol’s ETS. Other units which may be transferred under the scheme may be in the form of:

-

•Removal Unit (RMU) from Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF)

-

•Certified Emission Reduction (CER) from a Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) project

-

•Emission Reduction Unit (ERU) from a Joint Implementation (JI) project

Transfers and acquisitions of all units are tracked and recorded through the registry system under the Kyoto Protocol and an international transaction log manages transfer of units between countries.

Several Articles of the Kyoto Protocol make provisions for the inclusion of LULUCF activities as part of efforts to meet national emission limits. It allows net changes in GHG emissions through direct human-induced LULUCF activities (afforestation, reforestation , deforestation, forest management, cropland management, grazing land management and revegetation that occurred since 1990) to be used to meet national emission reductions for the first commitment period.

Australia is one of a few countries (listed in Annex 1 of the Protocol) to which this LULUCF provision is allowed and it is often referred to as the ‘Australia Clause’ in the Protocol. LULUCF activities resulting in a net removal of GHGs means the nation can issue Removal Units (RMUs) as part of meeting its commitment. Australia’s allowed national increase in emissions to 8% (rather than 5%) above 1990 emissions levels for the first commitment period 2008 - 2012 will be achieved primarily on the basis of LULUCF inclusion in the Kyoto Protocol.

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) allows for the implementation of LULUCF project activities in countries not listed in Annex 1 but is limited to afforestation and reforestation projects to generate CERs. These activities can assist countries to achieve compliance with their emission reduction commitments whilst simultaneously achieving sustainable development.

Joint Implementation (JI) means an Annex 1 country may implement projects that increase carbon sinks in another Annex 1 country and the Emissions Reduction Units (ERUs) generated from these projects can be claimed in meeting its national emission reduction target.

1990 was chosen as the base year for emissions comparisons and benchmark because it was considered the first year that sufficiently reliable baseline data was available, against which subsequent assessments of increases or reductions in emissions could be compared. Cynical analysts suggest the year was chosen because it was convenient for some powerful economies that were undergoing significant transition in their national emission profiles at the time.

The first act of the newly elected Prime Minister Kevin Rudd when sworn into office on the 3rd December 2007 was to sign the instrument leading to Australia’s ratification of the Kyoto Protocol.

The USA remains as the only developed nation not to have ratified the Kyoto Protocol.

The Copenhagen Accord in December 2009 is a document that the UNFCCC agreed to "take note of", and is therefore not legally binding. The Accord does not commit countries to a successor instrument to the Kyoto Protocol, whose present round ends in 2012. This was the cause of much disappointment surrounding the Copenhagen conference and its failure to secure new global binding limits through to the next commitment period.

Australia submitted its 2020 target range for the Copenhagen Accord in January 2010 and in December 2010 the pledges under that Accord were incorporated into the UN process through the Cancun Agreement.

What are other countries doing to reduce their emissions?

The Cancun Agreement (2010) represents pledges from countries representing more than 80 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions and 90 per cent of the world economy, including China, the United States, the European Union, India and Japan.

Globally, more money is now being invested in new renewable power than in new fossil fuel electricity generation and more than 85 countries have renewable energy targets either legislated or planned.

China is now the world’s largest manufacturer of solar panels and wind turbines and China has the most renewable energy generation capacity of any country.

The United States is moving to regulate carbon pollution, including from large industrial facilities. The ‘Clean Energy Standard’ announced by President Barack Obama aims to double the share of clean energy in America’s electricity supply by 2035.

Many countries have put a price on carbon pollution and introduced ETSs that create economic incentives for industry to reduce pollution. Some policies have been in place for many years. Thirty-one European countries — including the United Kingdom, Germany and France — have a price on carbon pollution through an ETS. New Zealand started emissions trading in 2008. Carbon taxes are also in place in the United Kingdom, India, Switzerland, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, Costa Rica and Ireland.

The primary goal of pricing carbon pollution is to decouple growth in emissions from economic growth. Pricing carbon provides a financial incentive to invest in low-emissions technology and carbon mitigation activities.

What is Australia’s response?

Emission projections show Australia is on track to meet our current commitment period target. However, our emissions have been growing and are projected to grow by approximately 2% per year. This means our emissions will be 24% above 2000 levels by 2020 and 44% above 2000 levels by 2030.

As the highest per capita emitter of greenhouse gases in the developed world and one of the 20 largest emitters on an absolute basis, Australia needs significant action if it is to limit emissions and comply with global agreements into the future.

In 2009, the Government expanded the Renewable Energy Target to increase Australia’s electricity supply to 20% from renewable sources by 2020. By the early 2020s, the amount of electricity from sources like solar, wind and geothermal will be almost as large as all of Australia’s current domestic electricity consumption.

On the 10th July 2011 the Australian Government announced a major new climate change policy called Securing a Clean Energy Future that included a new long term goal to achieve an 80% reduction on year 2000 levels by 2050. This brings the target reduction level in line with the positions also taken by Germany and the United Kingdom.

From 1st July 2012 the Government will impose a fixed price carbon tax on the 500 biggest carbon polluters in the Australian economy. The 50 largest polluters are responsible for around 75 per cent of the carbon pollution. The government will tax the 500 biggest polluters a fixed price of $23 for every tonne of CO2 equivalent emissions they produce for three years. From the 1st July 2015 the fixed carbon price will transition to a ‘cap and trade’ ETS in which the ‘flexible price’ stage, the carbon tax, will be set by the global carbon market.

The Australian Government is also implementing the Carbon Farming Initiative as part of establishing market-based mechanisms to encourage investment in carbon abatement activities in Australia. Established through the The Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Bill 2011 it enables farmers, forest growers and landholders access to domestic voluntary and international carbon markets, opening up abatement opportunities in the land sector, which currently account for 23 percent of Australia’s carbon emissions.

This will also align carbon abatement objectives with protection of Australia’s natural environment and improve resilience to the impacts of climate change. Improving water quality, reducing salinity and erosion, protecting and promoting biodiversity, regenerating landscapes and improving the productivity of agricultural soils will present important opportunities to reduce the global net greenhouse gas emissions.

get the free

Adobe PDF Reader

computer can’t read PDF files?

© 2015 Frontline Services Australia Pty Ltd | ABN 41 136 738 997 ACN 136 738 997 | E: info@frontlineservices.com.au